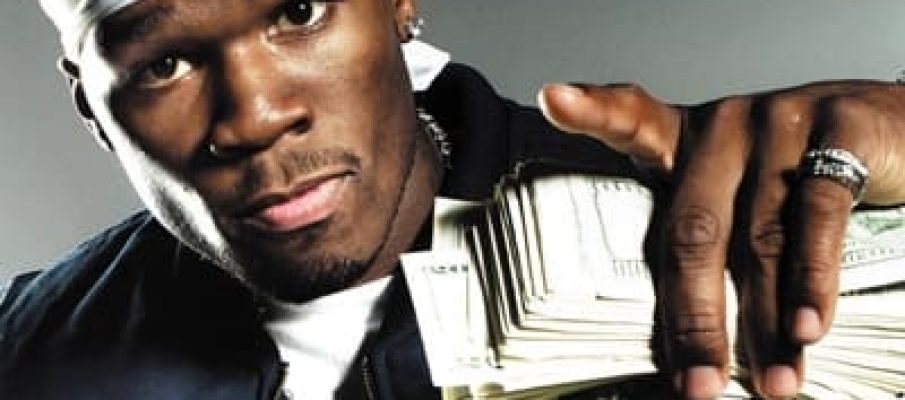

Sometimes the most meaningful lessons come from unexpected places. In this article, find out what helpful financial advice can be gleaned from the beats of hip hop.

‘Mo Money, Mo Problems’? 7 hip-hop financial lessons

Sometimes the most meaningful lessons come from unexpected places. In this article, find out what helpful financial advice can be gleaned from the beats of hip hop.

‘Mo Money, Mo Problems’? 7 hip-hop financial lessons

It sounds almost too obvious. Investment advisers tell you to buy low and sell high. So what’s the trick? The principle is that you should buy investments at a low price. When those investments rise in price, you should sell them. Most professionals save for their retirements, and they buy mutual funds rather than individual stocks.

The problem is that people often do exactly the opposite of what this conventional wisdom tells them. They listen to people talk about a “hot” investment. The buzz causes prices to rise. People enthusiastically rush in to buy the mutual fund. By that time, conditions have changed. The price falls. Disillusioned, the once enthusiastic investor takes the loss and dumps the investment. In other words, people buy high and sell low.

So what’s the solution?

The solution is actually rather boring, and it doesn’t make for good cocktail party conversation. Ordinary mortals should give up on the idea that they can “beat the market.” Investments are best made slowly and steadily over a long period. For people saving for retirement, a steady and substantial contribution to a retirement fund is a good idea. When the price rises, the same investment amount buys fewer shares. When the price dips, the funds are “on sale,” and you wind up with more shares. Over the long haul, markets tend to rise anyway.

When equity markets dip over 10%, experts call it a correction — and this has happened recently. Professionals looking at their hard-earned portfolios easily become discouraged. Some people decide to take refuge in the safety of money market funds and they sell their mutual funds.

That is exactly the wrong approach. The right approach is to hang in there and comfort yourself that you are buying more shares for your money as you continue to invest. The price averages out over time — and that is what advisers mean when they talk about dollar cost averaging.

This requires patience and discipline rather than a sharp eye for a hot investment.

The best thing about a good retirement plan like the one offered to employees of Johns Hopkins University is that we have a large number of ways in which we can invest our retirement money. But sometimes it seems as if that’s also the worst thing about the plan. There are so many choices that it’s sometimes confusing.

The choices usually boil down to choosing mutual funds. Not too long ago, someone told me that he wasn’t exactly sure what a mutual fund was!

A mutual fund pools money together from investors. A professional manager decides to invest that money based on the fund’s objectives. The idea works well for small investors, who may not want to risk buying individual stocks because doing so puts too many eggs in one basket.

For example, an investor might decide to invest in the 500 largest companies in the United States. That investor doesn’t have the money to buy stock in each of those 500 companies. A mutual fund manager uses the pool of money in the mutual fund and buys stock in these companies on behalf of the investors.

There are mutual funds that suit the purposes of almost any investor. For example, Vanguard (like many other investment firms) has a fund called the Vanguard 500 Index Fund that invests in America’s 500 largest companies. Other funds, like Fidelity’s Select Biotechnology Portfolio, buy into specific industry sectors. Other funds might invest in a particular country or region. For example, Fidelity has a Japan Fund and a Europe Fund.

Some mutual funds are designed to enable investors to keep their choices in line with their beliefs and values. For example, TIAA -CREF’s Social Choice Equity Fund favors companies that treat the environment responsibly, serve local communities, make high-quality safe products, and manage ethically.

There are even funds that specialize in “sin” stocks. The USA Mutuals Barrier Fund invests in tobacco, alcohol, weapons, and gambling!

A useful distinction is between index funds and managed funds. An index fund (like the Vanguard 500 Index Fund) buys blindly into America’s 500 largest companies. In contrast, managed funds carefully select stocks or bonds to maximize the returns for their investors. There are advantages to both strategies. Many people believe that it’s better to have a well-diversified portfolio rather than to make bets on particular countries, sectors, or regions. Others think it’s important to be able to take advantage of financial trends. Typically, a managed fund needs more analysts and experts, and the cost of hiring these people is often high. The Vanguard Index 500 Fund, for example, has an expense ratio of 0.17%, while the Turner Medical Sciences Long/Short Investor Fund has a net expense ratio of 2.2%. So you need to manage the risk of your returns being spent on these expenses.

We cannot advise you how to invest your money on this blog, but any financially savvy person will tell you to make sure of two things. First, make sure that a fund’s management costs are not too high. Second, make sure your portfolio is diversified across a broad range of sectors, countries, financial instruments, and strategies.

The biggest mistake investors make is to try to chase the hottest funds in the hope of “beating the market.” A slow, steady, and deliberate approach is the path to financial security. It’s boring, but it works!

Readers who’ve raised teenagers may be familiar with a conversation that goes something like this.

Teenager: Can I borrow $50? I’m going to a concert on Saturday. [Asking for money bypasses the customary request for permission to go to the concert. Clever!]

Me: [Trying to look a little serious. Possibly judgmental?] You really shouldn’t be spending money before you’ve earned it.

Teenager: [Touches the carpet with right foot. Hoping to appear assertive yet patient with a parent who may have cognitive limitations.] I have earned it. It’s just that I’m temporarily short of money.

Me: [Wondering which planet developed teenage logic.] What do you mean you’ve earned it?

Teenager: [Puts hands on hips. Too assertive? I am here to borrow – not to fight.] Well, I did that babysitting job last night. I made $100!

Me: [Knowing where the conversation is doing, but making one last ditch effort to preserve the contents of my wallet.] So, if you made $100, you should be all set. Right?

Teenager: [Tempted to roll eyes, squirms a little, shuffles feet.] No. I need $50. It’s just that Mrs. Jones said that she’d pay the $100 as soon as she came home last night. But she forgot to go to the bank…

Me: And…?

Teenager: So, I earned the money, but it’s kind of not in my hands right now. But it’s still my money.

Me: So, is that my fault?

Teenager: [Wondering whether this parent is incurably stupid.] Well, no. But I’ve been doing babysitting for Mrs. Jones for over a year now. I know she’s going to pay me. I just have to wait until I do babysitting for her again next Tuesday. [Removes hands from hips and look of defiance. Perhaps it’s time to grovel!] But I promise you that when she pays me, I’ll give it straight back to you. You know I always pay you back when this happens, and I’ve paid off every penny of what I owed you before. So I really have $100. Please lend me the money — this band is so awesome and this might be my only chance to see them play! Ever!

Me: [Careful not to establish a precedent.] Well… just this once…

Teenager: [Careful to establish a precedent.] Thank you! Thank you! I knew you’d say yes. It’s so nice to know you’re always there for me.

If the teenager had taken our course, “Accounting Comes Alive,” here’s how she might have presented the case:

My business is profitable. Last night I had income of $100 with no expenses whatsoever. On my balance sheet, I have assets, including a healthy set of accounts receivables totaling $100 from a reliable customer. I would like you to consider a loan of $50 to solve my short-term cash flow problem, creating a very reasonable total debt to total assets ratio of only 0.5.

You can expect repayment in full next Tuesday. Considering the accounts receivables I am offering as surety, my reliable track record of repayment, and the fact that there are no other liabilities on my balance sheet, and, of course, your undying affection for me in your capacity as my parent, I propose that this loan be free of interest. Perhaps, to save you the inconvenience of future loan applications and, of course, to make sure my future needs are met, we should treat this transaction as a revolving line of credit rather than a one-time loan.

The teenager understands quite a lot of things many adults have a hard time figuring out, including:

Johns Hopkins University employees who would like to understand these matters thoroughly can register for our course, “Accounting Comes Alive,” by clicking here. You will learn about balance sheets, income statements, and how business works. We will also talk about the university’s most recent financial statements.

Let’s pretend it’s March 1, 2015, and you have two JHU faculty members who both received retroactive raises in letters from the promotion committee dated March 1, 2015. Dr. Einstein’s raise is effective November 1, 2014 (more than 90 days ago) and Dr. Watson’s raise is effective January 1, 2015 (less than 90 days ago). Both faculty are paid from sponsored and non-sponsored funds. Here’s how you (in the departments) deal with each situation.

Retroactive by more than 90 days — Dr. Einstein (Raise Date: November 1, 2014)

Retroactive by less than 90 days — Dr. Watson (Raise Date: January 1, 2015)

NOTE: The Cost Distribution section of a Salary Change ISR differs from the Cost Distribution section of an E-form. In the Cost Distribution section of a Salary Change ISR, the total of all the cost-distribution lines must equal the semi-monthly amount. In an E-form Cost Distribution section, you may enter multiple periods at different rates for the same account.

In both cases above, HRSS will have the salary difference allocated to the control salary account if the new cost distribution does not match the new semi-monthly amount and/or does not cover all the retro pay periods.

For more information, review the following:

Sponsored funds procedure for JHU semi-monthly faculty, staff, and students

Today I was teaching the Accounting Comes Alive course, and a number of the people in the group were unfamiliar with the concept of deferred revenue. They also seemed unsure about why it is found in the Liabilities area of a balance sheet. Why, they reasoned, should revenue be a liability?

Perhaps the first confusing thing is that when people think about liabilities, they think only about money. A liability, however, can be an obligation to an outside entity either to pay or to perform. For example, when you borrow money from a bank, you have an obligation to pay it back. That’s a very simple kind of liability, and it involves only money.

Suppose you buy an airline ticket. You haven’t really bought anything tangible. Rather, you have bought a promise by the airline to transport you from point A to point B. In other words, the airline has an obligation to perform the service of transporting you. And if the airline is unable or unwilling, you have the right to ask for your money back. That is the essence of deferred revenue. It’s an obligation usually created when a customer pays for a product or service in advance. A prepaid card for a coffee chain is another good example. You have given the company some money, and they are now indebted to you in the form of coffee.

When it comes to a university, a good example is tuition. The tuition is paid up front. Once the money is paid, the university owes the student educational products and services. If a grant is paid before services are delivered, a university would consider the services to be a liability until the promise is fulfilled. These obligations to perform appear on the university’s balance sheet as deferred revenue.

Concepts like these are explored in the class, Accounting Comes Alive.

If you’re a Johns Hopkins University employee, you can sign up for the class by clicking here.

My voice has been quiet on the blog over the past few months due to a big project we are feverishly working on – transitioning from BW to Analysis in SAP.

What is SAP/BW/Analysis?

SAP is an enterprise resource planning software that we use at Hopkins to manage business operations.

One of the reasons we use SAP is to have a tool that can run reports. We run reports on everything here at Hopkins. From sponsored projects to HR demographics, we need reports to show us how we are spending and where we can save, and to demonstrate compliance. Therefore, it’s important we use the most up-to-date and robust tool to fulfill all of our reporting needs.

When we started using SAP, we used a front-end interface called BW Report Center to access data and reports in Business Warehouse. Technology has advanced and SAP has been changing their product. With that, they will no longer support the BW interface we are accustomed to using, but instead, have created a much more robust interface – Analysis.

Benefits of Analysis

We are really excited to transition over to Analysis for several reasons, including:

What does this mean for users?

Our project team has been creating a multitude of training opportunities for our users here at Hopkins. From FastFacts to job-aids to show-me videos to instructor-led training, we are trying to make sure we provide all of our users with training materials that best fit their personal learning style.

For more information concerning BusinessObjects Analysis and/or the upcoming training, please visit our Analysis resource page: http://finance.jhu.edu/reports_guides/analysis/overview.html

If you are an employee of Johns Hopkins University and have any additional questions, please email the Financial Quality Control department at Hopkins: fqchelp@jhu.edu