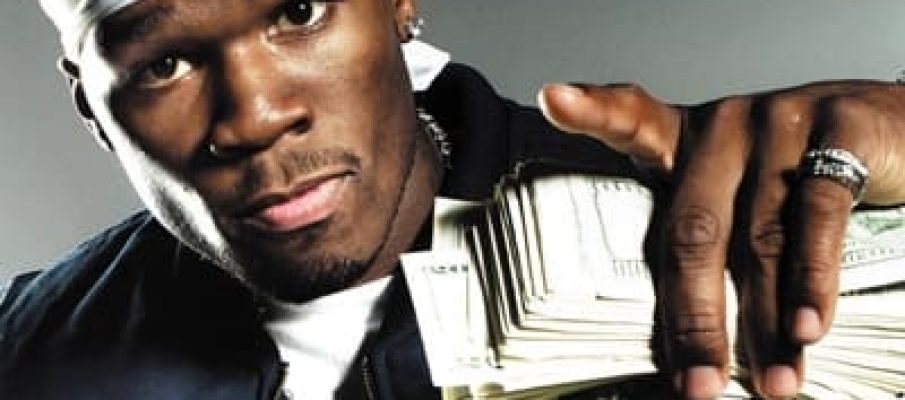

Sometimes the most meaningful lessons come from unexpected places. In this article, find out what helpful financial advice can be gleaned from the beats of hip hop.

‘Mo Money, Mo Problems’? 7 hip-hop financial lessons

Sometimes the most meaningful lessons come from unexpected places. In this article, find out what helpful financial advice can be gleaned from the beats of hip hop.

‘Mo Money, Mo Problems’? 7 hip-hop financial lessons

In a previous post, I discussed what a mutual fund is.

Today’s post describes another financial instrument, the ETF. ETF stands for Exchange Traded Fund. An ETF is very much like an index mutual fund, the kind of fund that buys into a market index rather than actively trying to outperform the market.

There is one very important difference, however. A mutual fund cannot be bought and sold on the fly in the way a stock can. With a mutual fund, you put in your order, and the trade is executed at the end of the next trading day. Many mutual funds have other ways of discouraging investors from behaving like traders.

With an ETF, you can behave like a trader. You buy and sell your ETFs just like stocks. For example, in the middle of the day, you hear some bad news and you learn that financial markets have dipped because of the news. You believe that the dip is only very temporary, and you speculate that the markets will return to normal after the dust has settled. You can buy in the morning and sell in the afternoon. Commissions tend to be low, and the internal costs of running an ETF tend to be low as well.

Some people avoid ETFs because they prefer the restricted world of the more boring mutual funds. Perhaps the biggest mistake investors make is to begin to speculate rather than invest. The flexibility of an ETF encourages people to speculate, and some think that’s a flaw.

The best thing about a good retirement plan like the one offered to employees of Johns Hopkins University is that we have a large number of ways in which we can invest our retirement money. But sometimes it seems as if that’s also the worst thing about the plan. There are so many choices that it’s sometimes confusing.

The choices usually boil down to choosing mutual funds. Not too long ago, someone told me that he wasn’t exactly sure what a mutual fund was!

A mutual fund pools money together from investors. A professional manager decides to invest that money based on the fund’s objectives. The idea works well for small investors, who may not want to risk buying individual stocks because doing so puts too many eggs in one basket.

For example, an investor might decide to invest in the 500 largest companies in the United States. That investor doesn’t have the money to buy stock in each of those 500 companies. A mutual fund manager uses the pool of money in the mutual fund and buys stock in these companies on behalf of the investors.

There are mutual funds that suit the purposes of almost any investor. For example, Vanguard (like many other investment firms) has a fund called the Vanguard 500 Index Fund that invests in America’s 500 largest companies. Other funds, like Fidelity’s Select Biotechnology Portfolio, buy into specific industry sectors. Other funds might invest in a particular country or region. For example, Fidelity has a Japan Fund and a Europe Fund.

Some mutual funds are designed to enable investors to keep their choices in line with their beliefs and values. For example, TIAA -CREF’s Social Choice Equity Fund favors companies that treat the environment responsibly, serve local communities, make high-quality safe products, and manage ethically.

There are even funds that specialize in “sin” stocks. The USA Mutuals Barrier Fund invests in tobacco, alcohol, weapons, and gambling!

A useful distinction is between index funds and managed funds. An index fund (like the Vanguard 500 Index Fund) buys blindly into America’s 500 largest companies. In contrast, managed funds carefully select stocks or bonds to maximize the returns for their investors. There are advantages to both strategies. Many people believe that it’s better to have a well-diversified portfolio rather than to make bets on particular countries, sectors, or regions. Others think it’s important to be able to take advantage of financial trends. Typically, a managed fund needs more analysts and experts, and the cost of hiring these people is often high. The Vanguard Index 500 Fund, for example, has an expense ratio of 0.17%, while the Turner Medical Sciences Long/Short Investor Fund has a net expense ratio of 2.2%. So you need to manage the risk of your returns being spent on these expenses.

We cannot advise you how to invest your money on this blog, but any financially savvy person will tell you to make sure of two things. First, make sure that a fund’s management costs are not too high. Second, make sure your portfolio is diversified across a broad range of sectors, countries, financial instruments, and strategies.

The biggest mistake investors make is to try to chase the hottest funds in the hope of “beating the market.” A slow, steady, and deliberate approach is the path to financial security. It’s boring, but it works!

People who invest often want to know how much money they will have when they actually need it. Unfortunately, it’s hard to calculate that in your head because of the compounding effect when an investment grows.

Someone came up with “The Rule of 72.” This makes it a lot easier. Supposing you are 26 years old. You have bought an investment for $5,000, and you believe its value will increase by 6% every year. You hope to retire when you’re 62 (36 years from now). You’re curious about how much money you can expect to see when you retire.

Here’s where the rule of 72 comes in. You take 72 and divide it by your projected return rate.

72 divided by 6 = 12.

Twelve is the number of years it will take for your investment to double.

So you can expect your money to grow as follows:

| Year | Age | Value |

| 2015 | 26 | $5,000 |

| 2027 | 38 | $10,000 |

| 2039 | 50 | $20,000 |

| 2051 | 62 | $40,000 |

The Rule of 72 is a useful trick to project investment value, but it does have its limitations. First of all, it’s an approximation. Second, it’s next to impossible to predict the performance of any investment. You should be especially wary of using the past to predict the future.

There are several things people should think about as they plan for retirement:

Today I was teaching the Accounting Comes Alive course, and a number of the people in the group were unfamiliar with the concept of deferred revenue. They also seemed unsure about why it is found in the Liabilities area of a balance sheet. Why, they reasoned, should revenue be a liability?

Perhaps the first confusing thing is that when people think about liabilities, they think only about money. A liability, however, can be an obligation to an outside entity either to pay or to perform. For example, when you borrow money from a bank, you have an obligation to pay it back. That’s a very simple kind of liability, and it involves only money.

Suppose you buy an airline ticket. You haven’t really bought anything tangible. Rather, you have bought a promise by the airline to transport you from point A to point B. In other words, the airline has an obligation to perform the service of transporting you. And if the airline is unable or unwilling, you have the right to ask for your money back. That is the essence of deferred revenue. It’s an obligation usually created when a customer pays for a product or service in advance. A prepaid card for a coffee chain is another good example. You have given the company some money, and they are now indebted to you in the form of coffee.

When it comes to a university, a good example is tuition. The tuition is paid up front. Once the money is paid, the university owes the student educational products and services. If a grant is paid before services are delivered, a university would consider the services to be a liability until the promise is fulfilled. These obligations to perform appear on the university’s balance sheet as deferred revenue.

Concepts like these are explored in the class, Accounting Comes Alive.

If you’re a Johns Hopkins University employee, you can sign up for the class by clicking here.

“Accounting Comes Alive” is a very popular one-day course that will empower you by strengthening your understanding of accounting and financial analysis. The information that you learn in this course will help you do your work, make informed decisions, and understand the effects of financial transactions on the enterprise.

Although at first this seems like an accounting course, ultimately, it’s about business. The idea behind the course is not to teach you how to become an accountant, but rather to understand our business better. You will learn how the non-profit world of Johns Hopkins differs from the for-profit world, and you will also learn about the similarities.

We start by developing an accounting framework to build accounting literacy. We then manipulate objects to represent transactions to give you a profound understanding of the effect of transactions on the whole enterprise. Finally, we engage in conversations that will build your business acumen.

Presented as a series of conversations, the course explains how accounting is about organizing information to make it useful. You will learn a metaphor that uses color to explain how accounting tracks the flow of funds in an organization.

This is not a hands-on course designed to teach you to use SAP or Business Warehouse.

To view or register for an upcoming session, go to: http://lms14.learnshare.com/l.aspx?Z=z8i1IZSGIIDPnoFGYm%2bv4NnFzSkJWC6fGlguiNV7te4%3d&CID=89